The rise and fall of Jimmy Lai, whose trajectory mirrored that of Hong Kong itself

On Monday, a Hong Kong court convicted Jimmy Lai of national security offences, the end to a landmark trial for the city and its hobbled protest movement.

The verdict was expected. Long a thorn in the side of Beijing, Lai, a 78-year-old media tycoon and activist, was a primary target of the most recent and definitive crackdown on Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. Authorities cast him as a traitor and a criminal.

Lai’s trial was one of the last unfinished national security prosecutions of Hong Kong’s high profile activists, over their involvement in the 2019 protests. Hundreds of activists, lawyers, and politicians have been pursued and jailed, or chased into exile. But few have captured global attention like Lai, whose life and career has developed in tangent with Hong Kong’s sputtering walk towards democracy, and then its fall.

“The trajectory of his life reflects the history of Hong Kong itself,” said Kevin Yam, a Australian-Hong Kong lawyer, who is subject to a Hong Kong arrest warrant for his pro-democracy activism.

A prison van carrying Jimmy Lai drives to the West Kowloon magistrates courts for the closing arguments in his national security trial on 18 August, 2025, in Hong Kong. Photograph: China News Service/Getty Images

Lai had pleaded not guilty to the one count of conspiracy to publish seditious publications and two counts of conspiracy to foreign collusion. On Monday the court found him guilty of all charges, with the government-appointed judges saying he “had harboured his hatred and resentment for the [People’s Republic of China] for many of his adult years”, and sought the downfall of its ruling Communist party “even though the ultimate cost was the sacrifice of the people of the PRC [People’s Republic of China] and HKSAR [Hong Kong Special Administrative Region].”

The trial stretched for nearly two years, beset by delays, legal challenges and government interventions. International rights groups had called it a politically motivated show trial, and an attack on press freedom.

Lai has been behind bars since 2020, either on remand or serving the five separate sentences he has been given for protest-related offences totalling almost 10 years, and a fraud allegation his supporters say was trumped up.

Monday’s convictions could see him given a life sentence. His family already fears he might not live to see freedom. In the weeks before the verdict, his children issued new alarming warnings over his health.

From child labourer to ‘Rupert Murdoch of Asia’

Lai’s rise to become one of the city’s most famous billionaires is a rags to riches tale. At 12 he left Mao’s China for Hong Kong, where he worked as a child labourer in garment factories, before building a business empire that included the retail chain Giordano, and then a media conglomerate that would see him nicknamed the “Rupert Murdoch of Asia”.

A copy of the Apple Daily newspaper in Hong Kong in August 2020, with a front page photo of its founder Jimmy Lai being escorted through the paper’s newsroom by police. Photograph: Yan Zhao/AFP/Getty Images

At the time of his first arrest in 2020, Lai was worth an estimated $1.2bn, according to a biography written by longtime friend and associate Mark Clifford. But he was one of the few of Hong Kong’s elite who used their power and wealth for activism, funding and participating in pro-democracy and anti-authoritarian efforts.

Many of Lai’s business milestones are tied to key events in the history of Hong Kong and China’s tug of war over democracy, although he wasn’t always political. His son Sebastien says his early business decisions were driven by ambition and boredom.

“I always remember growing up he he talked about why he started Giordano, and he was like, look I just got bored,” said son Sebastien.

But after Chinese troops massacred student protesters in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989, Lai became politically radicalised, and he launched Next Magazine soon afterwards. The Apple Daily newspaper was established shortly before Hong Kong’s handover from UK rule to China, upending the city’s traditional media market with flashy tabloid reporting and gossip alongside fearless investigations.

“It kept Hong Kong honest in many ways,” says Yam. “We kind of forget that Jimmy Lai and his media businesses played an important role in Hong Kong as an international financial centre because it kept the free flow of information going about Hong Kong’s corporate underbelly.”

A supporter holds an apple and a copy of the Apple Daily newspaper outside the court to support Jimmy Lai in October 2019. Photograph: Lam Yik/Reuters

The outlets Next Magazine and Apple Daily, along with Lai, would become loud and unashamedly pro-democracy irritants to authorities. Lai himself would write columns, famously calling China’s premier Li Peng, known as the Butcher of Beijing for his role in the massacre, “a bastard with zero IQ” in 1994, drawing political and financial retribution from the Chinese state.

In 2003, the two outlets supported protests against a proposed national security law for Hong Kong, in 2014 they backed the Occupy Central movement, when Lai also joined the protest camp. He was attacked by assailants who poured pig offal over him, and anti-corruption police raided his home and that of his top aide, Mark Simon, after leaked documents revealed he’d donated millions to activists.

In 2019 the papers again backed mass protests, this time against a proposed extradition bill but later building into a major pro-democracy movement. Apple Daily published a cut-out letter to US president Donald Trump on its front page, which readers could send to Washington asking him to “help save Hong Kong”. It would become a key element of the prosecution’s national security case against Lai.

Martin Lee, left, the founding chairman of the Democratic party in Hong Kong, sits beside Jimmy Lai in 2015 in Victoria Park at a candlelit vigil to mark the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. Photograph: Lucas Schifres/Getty Images

Lai again personally attended protest events, including a banned vigil for Tiananmen in June 2020, where he stood outside his car and held a lit candle, for which he was convicted and sentenced to 13 months in jail.

‘For them, I am a troublemaker’

Throughout his adult life in Hong Kong he was often monitored, harassed and intimidated. The blowback from the Li Peng editorials ultimately led to Lai divesting from Giordano. His house and businesses were repeatedly firebombed, and his family followed by paparazzi. In 2008 he was the target of a foiled assassination plot.

“For them, I am a troublemaker,” he told Clifford. “It is hard for them not to clamp down on me and silence me.”

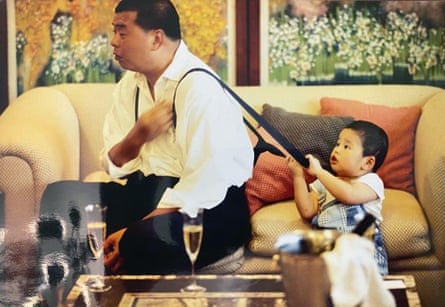

A young Sebastien with his father, Jimmy Lai. Photograph: Supplied

Sebastien, who now lives outside Hong Kong to lobby for his father’s freedom, says he wasn’t totally aware of the threats when he was young because his father never showed fear.

“I always had the knowledge that my dad was doing the right thing and not the easy thing” says Sebastien.

“You have someone who is, by all accounts, successful, but willing to give everything that he has for his beliefs. That in some sense would shame some people and therefore some people would not like him because of that.

“He always had the advantage that he came from nothing. He also had the advantage of knowing that even with nothing he’d be OK.”

Lai refused entreaties to get a bodyguard, saying he hadn’t done anything wrong. A bodyguard also couldn’t help against his biggest risk: arrest.

After 2019, that risk came to fruition multiple times. In August 2020, just weeks after the introduction of the Beijing-designed national security law (NSL), hundreds of police officers stormed the offices of Apple Daily. They arrested Lai along with several Apple Daily executives under the sweeping new law against dissent. His two eldest sons, Ian and Timothy, were also arrested. The company was ultimately forced to close the following year.

Sebastian Lai speaks at a press conference outside Downing street in London in September 2025. He feels the UK didn’t push hard enough for the release of his father, a British citizen. Photograph: Henry Nicholls/AFP/Getty Images

The closure of Apple Daily, yet another nail in the coffin of democratic Hong Kong, was splashed across front pages around the world. The paper was a controversial tabloid, publishing salacious stories and occasionally offensive opinion pieces about mainland Chinese people. Former employees, who testified against Lai as “accomplice witnesses”, alleged a working environment that was free but “within a bird cage”, under the close management and control of Lai, with editorials written with the understanding that they “had to follow the basic stance of the newspaper”.

But, Sebastien says, “in the end Apple is the only newspaper who stood up for democracy in Hong Kong, throughout the whole time, right?”

In defiance of Lai’s arrest and the paper’s closure, Hongkongers queued up to buy an estimated 1m copies of the paper’s final edition. China’s nationalistic Global Times paper praised the closure of the “secessionist tabloid”.

‘They haven’t bitten yet … so let’s see what happens’

Friends and advisers had urged Lai to take advantage of his UK citizenship, wealth, and foreign residences and flee the country, like many others had. He refused, saying he wanted to stay and support his journalists, and to keep fighting for Hong Kong.

He told Clifford he preferred to go to jail than abandon the city that “gave me everything”.

Jimmy Lai takes part in a sit-in called ‘Occupy Central’ or ‘Umbrella revolution’ in Hong Kong, in October2014. The movement that began in response to China’s decision to allow only Beijing-vetted candidates to stand in the city’s 2017 election for chief executive. Photograph: Lucas Schifres/Getty Images

While out on bail he gave interviews, and launched a livestreamed political talk show. Speaking to the Guardian during that time, Lai was cautiously optimistic, noting the NSL was yet to be fully tested in Hong Kong’s – at the time, still internationally lauded – court system.

“They just want to show the teeth of the national security law, but they haven’t bitten yet,” he said. “So let’s see what happens.”

They did bite. What happened was more than 200 NSL arrests; a mass prosecution of 47 politicians, activists and civil society workers who held an informal vote before city elections; appeals to Beijing when the courts didn’t toe the government line; and laws rewritten to limit bail rights and restrict foreign lawyers from defending Lai.

Lai was reportedly held in solitary, and denied communion as a devout Catholic. Authorities pushed back on such criticisms, saying it was a matter of logistics or even a request by Lai. When Lai was photographed looking gaunt in shorts and sandals in the yard at Stanley prison by an Associated Press photographer with a long lens, the jail built a new roof covering. The photographer, Louise Delmotte, was later barred from working in Hong Kong when her visa renewal application was rejected.

One fear that was never borne out for Lai was a clause in the NSL that the most serious cases could be transferred to the mainland for trial. If they were going to do it for anyone, it would be Lai, observers figured. He had already been treated like the city’s most dangerous criminal, taken to court in December 2023 by armoured convoy, with security “one would expect for a president or a high-profile terrorist”, Clifford’s biography notes.

The Trump connection

At the heart of the prosecution were Lai’s business and political connections, particularly with US officials.

Prosecutors wheeled out a crude Powerpoint-style presentation of “external political connections” with whom Lai had allegedly colluded. It included Trump, Trump’s former vice-president Mike Pence and former secretary of state Mike Pompeo, and veteran Democrat legislator Nancy Pelosi. All were known China hawks and during Trump’s first term had toughened US policy towards China in a way that analysts said put real pressure on Beijing over human rights abuses.

Trump has repeatedly promised to lobby for Lai’s release and officials said the media mogul’s case was raised in the meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping in South Korea in October. But in his second term, Trump’s America First agenda has become even more extreme, alienating allies, and his position on China more focused on “making a deal”.

Some have speculated that this may turn Lai into a bargaining chip in the US-China trade war.

Jimmy Lai holds a banner as he marches along Queen’s Road Central during a 2019 protest. Photograph: Bloomberg/Getty Images

After the South Korea meeting, Sebastien publicly thanked the US president and praised him as the “Liberator in Chief”, a moniker that conservatives bestowed on Trump after the release of hostages from Gaza.

Sebastien’s appeal to Trump stems in part from what he sees as the failure of the UK government to push hard enough for the release of his father, a British citizen.

The UK government has called for Lai’s release and says that his prosecution is politically motivated, but has not taken any economic action against Hong Kong. In the year to July, bilateral trade between the two territories reached £27.2bn, a nearly 10% increase on the previous 12 months. Many Lai supporters feel the UK has not done enough to secure the release of one of its most prominent citizens in its former colony.

Were Jimmy Lai released today, Hong Kong would look very different to what he last knew, says Sebastien.

“It’s obviously no longer the sort of Hong Kong that had all these freedoms that you could associate with,” he says, caveating that he’s not there either now, and can’t return.

“Obviously, I think he’d be quite sad about what’s happened but look, at the end of the day this is someone who’s done everything he can, right? I don’t think anybody looking at his life would think: well, he could have done more.”